Beginnings

Beginnings

Our story, which begins very far from Halkidiki and Mount Athos, takes us back several decades to the beautiful town of Trikala and to its surrounding villages. In the 1960s, when monasticism in Greece had entered a period of decline, a group of young men set out on the difficult life journey of monastic withdrawal in the high, solitary peaks of the Meteora. These zealous youths had been inspired by the teachings of their Elder, Archimandrite Aimilianos, then abbot of the Transfiguration Monastery (or ‘Great Meteoron’). At the same time, a company of young women also came to the same momentous decision to follow the monastic life, all of them also spiritual children of Fr Aimilianos.

Both communities installed themselves in monasteries on the awe-inspiring monoliths of the Meteora—the men at Holy Transfiguration and the women at a much smaller house named after the two Saints Theodore. Theirs was a common goal: ‘…the salvation of souls; that perfection which is elevating and pleasing to God, and blessed deification’1. In spite of their enthusiasm for the region, it was not meant for them to remain at the Meteora. Seeking a quieter place, Elder Aimilianos and his young monks left for Mount Athos in 1973 to populate and revitalize the almost -deserted Monastery of Simonopetra. This historic cloister, built during the 13th century by the Righteous Simon on a rock where he was shown the star of Bethlehem, is undeniably the most breathtaking and extraordinary edifice on the Holy Mountain. A towering building of seven storeys, it overhangs an enormous Athonite precipice. In the wake of recurring catastrophic fires (especially those of 1626 and 1891), the monastery had become destitute of monks. The arrival of the Meteora community in 1973 once more filled the monastery church with hymns and prayer. The cosy warmth of burning candles, the thick fragrance of the incense, and the prayers of the youthful monks re-animated the desolate rock. Elder Aimilianos and his new brotherhood offered a breath of fresh air to monasticism on Mount Athos by contributing to a renewal that, after the late 1960s, flowered in the ‘Garden of the Mother of God’.

With the fathers on Athos, the sisters, now numbering around forty novices, sought for themselves a permanent home, ideally close to the Holy Mountain. This was the beginning of a very difficult transitional period. But under the watchful eye of the Elder and of his monks a solution was soon to be found.

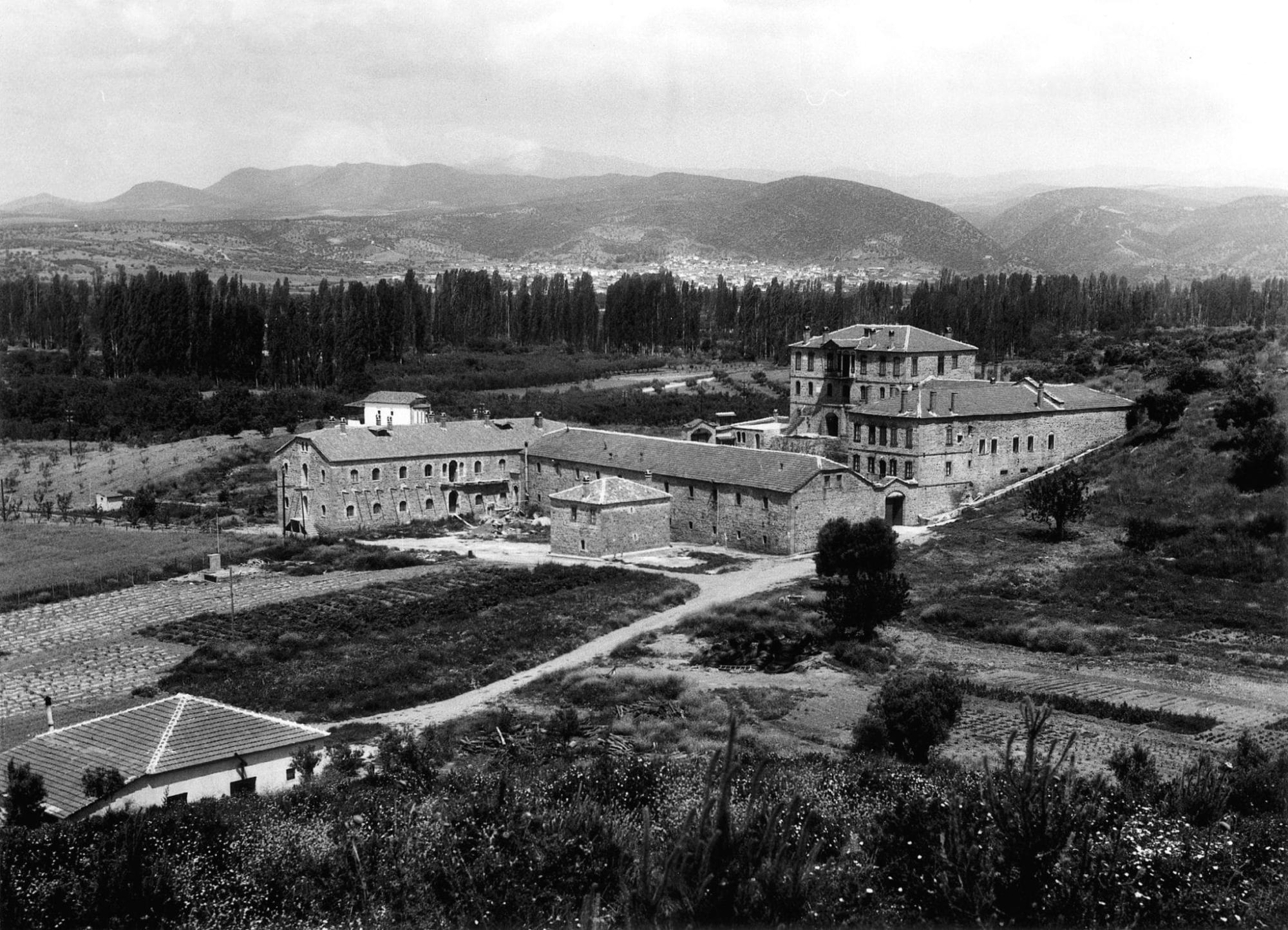

Before 1974 Vatopedi’s metochion in Ormylia was regularly occupied in the winter months by a group of Sarakatsani shepherds together with their numerous flocks. In due course negotiations were put in motion, money was found, and on 20 April 1974 the Ormylia dependency was transferred to Simonopetra. The sisters could now come and install themselves as a community in an Athonite daughter-house.

Seeking a home, the sisters fell upon a wasteland. The metochion was a cross between an untended sheep-pen and utterly squalid ruins: stone skeletons of unkempt buildings whose doorless and windowless openings gaped darkly into the courtyard. At best they provided night shelter for birds and snakes. Serpents, bats and owls had co-habited with the nomadic Sarakatsani. The sisters were not at all disheartened by this scene; they knew full well that the great monastic saints of the past had dwelt in places of greater destitution than this. Arming themselves with courage and enthusiasm for the challenge of monastic life, this brave army of young women set out to make of this wasteland a habitation: their own personal desert.

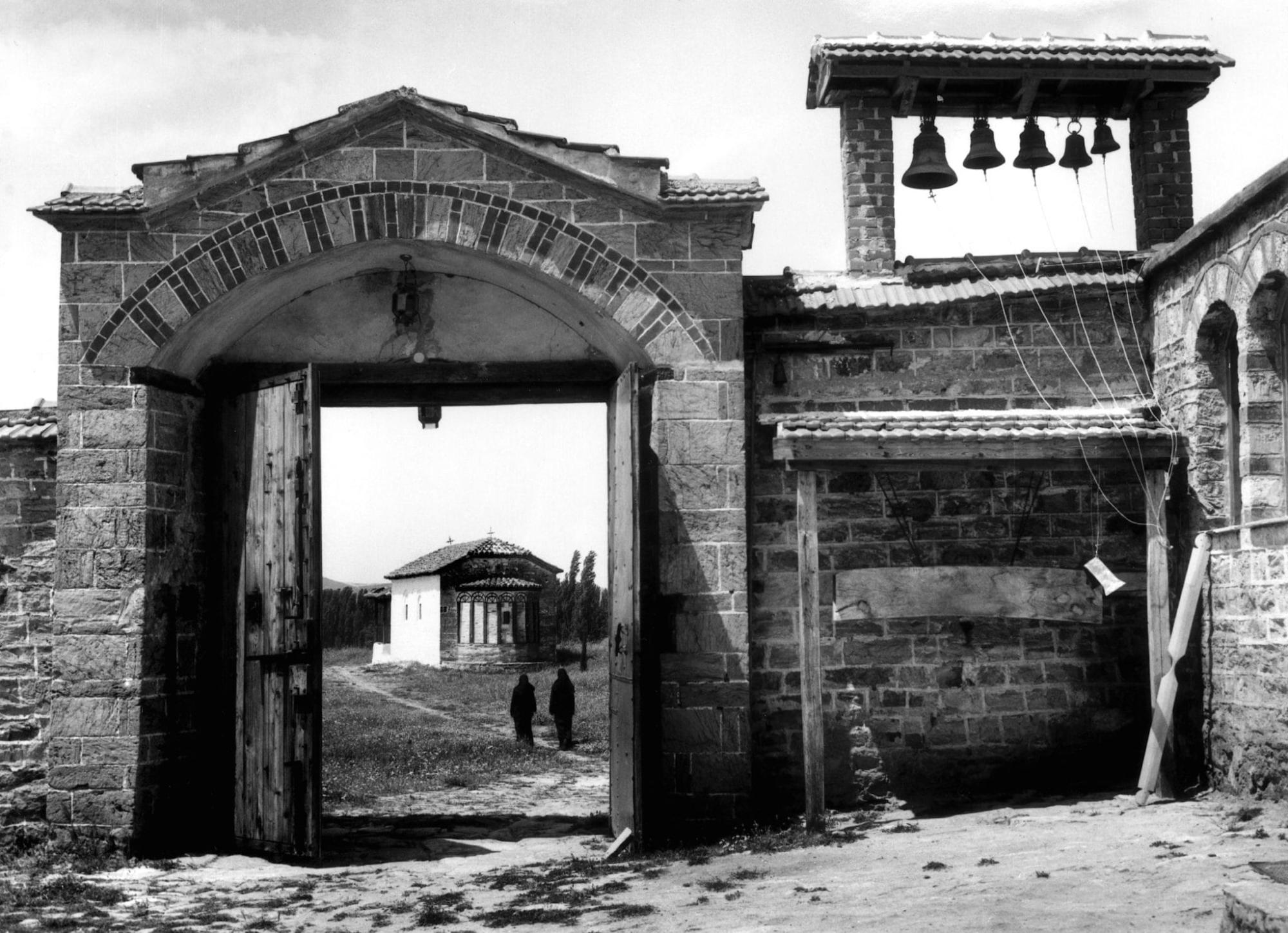

The first Divine Liturgy was celebrated in the old Chapel of the Annunciation on 5 July 1974 – a symbolic day, the feast of Saint Athanasios the Athonite, founder of cenobitic monasticism on Mount Athos. On that day, the saint, from his celestial abode above Halkidiki, sent down his blessings on the ocean of toil into which the young sisters had plunged themselves in order to transform the wilderness into sacred space.

Leading these endeavours – both the practical and the spiritual – was the Abbess Nikodeme. She provided the necessary inspiration, joy and assurance on this path to monastic perfection. The fathers at Simonopetra, together with the late Metropolitan Synesios of Kassandreia, and the faithful peasants in the neighbouring villages, offered all possible assistance. In the light of their very meagre resources and the humble donations of the pious inhabitants in the area, it was certainly no small thing for the sisters to transform the neglected ruins into a monastic dwelling. In spite of appalling difficulties, those years are now remembered as being the most productive; the morale of the nuns strengthened like steel. All who came to know the sisterhood at that time speak of a beehive that toiled ceaselessly: building, restoring, and reforming the arid metochion. Never for a moment did anyone’s thoughts or hopes stray from the original and eternal goal of monasticism, with its deep and profound life of inner perfection and worship. Throughout this spiritual journey Elder Aimilianos was the guiding light for the cenobium. His teaching sealed every moment and every impulse. On 5 May 1975 he produced a Typikon which came to constitute the corner stone of the dependency’s monastic tradition.2 By his teaching he undergirded and motivated the nuns in times of immense pressure.3 His words were prophetic:

The building, now full of manure, will be full of souls that will glorify God, and in the materialism of our age will […] stand each day between earth and heaven, as if they are not humans of this world, but rather more like heavenly humans, like angels who have descended from heaven to teach us what God wants from us, He Who wants nothing more from us than to follow His law and to love Him.

To begin with, the best preserved building in the complex was converted into lodgings for the newly-established sisterhood. Instead of windows, frames of plastic covered the apertures in the walls. With much effort all of the manure was eventually removed from the courtyards, revealing the old cobblestone path. Walls were painted, floors were scrubbed, and little by little the old dependency took on the appearance of a monastery. In time, new novices were welcomed into the community. Wings were eventually added to surviving structures, and on 14 September 1980 the foundations of the central church were laid and blessed by Metropolitan Synesios of Kassandreia.

It was not long before people began to take an interest in these new developments. Trickles became crowds, to the point that it became necessary to build new guest quarters and a reception area. Auxiliary rooms were constructed: workshops, a refectory, more cells, gateways, etc. Modifications to the monastery grounds also continued and, in due course, it began to dawn on the new cenobium that it was, in fact, rekindling that ascetic flame which had once burned brightly in ancient

Sermyli, Kallipoli, Kastro, and in the brotherhood of Saint Euthymios. It was perpetuating the tradition of those Athonite monks who for centuries lived, prayed and gathered crops from the land. It was reviving the supplications of the besieged Christians in Halkidiki and continues to this day to raise the prayers of all humble people to their eternal Father.

On 25 October 1991, through a sealed letter, the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew recognised the Holy Cenobium of the Annunciation of the Mother of God at Ormylia as a Patriarchal and Stavropegic foundation.